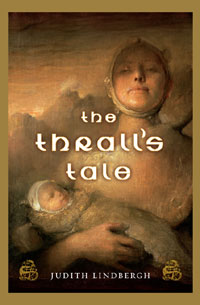

Excerpt from

THE THRALL'S TALE

by Judith Lindbergh

Chapter One

The Voyage

KATLA

Einar owns me, the runes at my collarbone speak from the carved stone, smooth with wear. The amulet belonged to another before me, another thrall whose name is lost. They don't remember even how she died, only that she did about the time that I was born. |

|

At my birth I was named for the fire burning beneath the mountain's ice, "Katla," and the string was tied, and so I have ever worn it. I have always been a slave.

Then why the unfamiliar sorrow that I am leaving the only land I've ever known, this land of my bondage? Yet I gaze about me almost mournfully as my master, Einar, stands upon the shore, tall among the circle of chieftains, setting the last of the plans before we see this place no more. The only one taller is Eirik Raude himself, his flaming head bright beside the others' mostly gray. It is he who planned this voyage to the great land to the west, beyond the open sea.

Serving at my master's banquet table two years ago at Yule, I heard Eirik tell of its lush pastures and its deep fjords brimming with walrus, seals, and birds. "So broad and vast and rich, friend Einar," he said. "Think on it! Think, if you dare, to come. Already there's a fjord named for you. I've set it so myself - Einarsfjord! - all rich and green, the fairest farm save perhaps my own - and set beside mine, with naught between our mighty homesteads but a pasture thick with grass and moss so fresh, sprouting up to make your cows' milk sweet and your sheep fat enough to slaughter even before the springtime's melted snows."

"You say 'tis such . . . ?" I saw my master raise a grizzled brow. "Well, to think on it. There's naught so fine about this Iceland now. Thick it is with homesteads, and only the lowliest grounds left upon the ashen hills - barely enough to feed our sheep, yet quick run thick with blood and feud if others have first claimed it. Your talk is tempting, Eirik, almost too fair to be believed."

"Yet you know me well, Einar."

"That, old friend, I do. I would not cross you in a fight, or when you're hard at drinking. Yet I'll tell you, you are mostly honest, if hard-tempered. For this, I'll think upon your offer and speak of it with my mistress, Grima. Yet what shall I tell her is the name of this new place?"

"Ah," Eirik Raude full-smiled then, his teeth rough-chipped, yellowish some, and broken in his ruddy beard. "Greenland." Slowly Eirik Raude did muse.

"Greenland." And the sound of it, so thick and fresh and hopeful on my master's tongue. So, and now, many months long past, we are set about to go.

I wait with the other thralls in a line before the plank. Einar's hefty trader's ship keens chorus with the other knarrs: twenty-five in all, each with bright-painted shields of wood and clanking metal hung upon their low-slung rails, and outstretched, dripping oars. Each is set to be captained by another master: Hafgrim, Herjolf, Ketil, Hrafn, even Helgi Thorbrandsson among their lot, all powerful here in Iceland once, but pushed out by hunger, vengeance, greed. They and all their households, their wives and sons, daughters and married kindred, and all their thralls, like me, packed to go to sea.

Such a crowd. All about are bondsmen's scalps - bald pates, shaved and shining as this morning's spring-ish dew - while we bonded women wear our best and only sheath of wadmal cloth, gray and drab and of a sweaty woolen, with a flaxen kerchief tied around our brows and braids. Nay, we look yet all the same, all dull and soiled, reeking, worn threadbare upon our elbows, while the freemen and their ladies nearly dance upon the Breidafjord rocks, flaunting all their finest, thickest woolens, their boots of fur and leather, their cloaks of seal, reindeer skins, and sometimes even bear with claws, all cheered and tucked and warm, set about to face the sea's fierce chill.

The knarrs rock to and fro, jolted by each foot stepping cautiously from plank to deck. Beneath, the fjord's waters brew up darkly. Barely I raise my chin above my bundle - small and coarse, it holds all that I possess. I press it tightly to my bosom. My heart pounds against it. Already, my skin is cold.

We crowd of thralls are thrust about. Upon a shouting, "Off!" we are pressed to let a horse, heavy-laid with bundles, pass. It steps upon the planking board, which sags, groaning loudly.

"Oh, 'twill break!" sudden the other thralls quick-whisper. "Or sink the ship!" "Nay, I'll not ride upon it." "Nor step - not another foot aboard."

The master's thrall's-watch hears us. He comes, heavy with his step, a seal's-gut cord twined about his fingers. "Hush you - all of you! Or upon your backs will fall our fate, as swift and ill as the whim of the weaving Norns."

The fateful Norns - three weaving ladies. So we're told they weave even upon the Norse gods' fate. Old One-Eyed Odin, Frey and Freya, Frigga, and Thor, and even Loki fear them! I like it not to think upon them now, upon this coast, before this swaying board.

Yet the foreman's words hush up the rest. The horse passes from the planking, settling in the hull of our master's ship. More they load the knarrs, ever tighter with cattle, boxes, trunks, bags of meal and seed, packets of skin, and coiled rope. Around me, braying goats and sheep soil bundles we packed just last night or many weeks before, while the sea laps still and hungrily upon our clamor.

From the first, there had been talk of dread upon this trip - thralls' talk, mostly - all fired up and wary. Grumbles, grunts, and reluctant groans from those who feared to stay or those to go. Well we knew Einar could not take us all. He would choose, and many terrored they'd be sold away. They trembled at their fate, looked about askance, plotted some, and planned and fretted mostly. I think I alone did not wonder much, for I knew then where my mother went I would surely be. And she would be with Einar. She had been his favorite - even until the day she died.

So, last spring, as I chored upon the hill watching old ships in the fjord raised up and repaired and fresh logs hewn to build new knarrs, I began with some excitement - and much unexpected dread - to realize we would truly leave this Iceland. Some say life is always better far away, where a slave might be freed if he proved his worth, or at least free to do somewhat more as he pleased; but I say life here is all I know. What lies ahead I cannot see.

With last autumn, the real preparations began, the storing and packing of grain, and drying of fish, and brewing mead, and catching fresh water from rains and streams in barrels lined with tar, and weaning lambs, and slaughtering sheep too old or sick to cross the ocean with us. And the selling of goods. I held the rag to catch my mistress' tears over her chest of heavy oak with its sturdy iron lock, from which she removed her fine-wrought linens and gauzy silks brought from afar, and tapestries stitched by her grandmother's hands, and other such treasures from her folk all long past, to be sorted, and many forsaken.

For me, there was cloth, too, to be woven for the sails. Had I known how hard and long and tedious the task, I might have thought to run away, but by the time I knew it, we were well into winter. There was nowhere to stray. Through the long nights and the cold, short days, we worked before the standing looms, weaving, ever weaving, until our arms ached, and our feet and our backs, and we could barely lift the threads. But at last the sails grew wide and strong. Just with springtime they were completed. We did not dye them as we might a Viking's sails, for these were not for raiding or battles, unless to win this foreign shore. But it is said there will be no one to conquer. Where we go there are no people, only ruins of campfires and strange tooled bones. Still, some speak of draugs in the night, dead walkers who would lure us to the mountain and madness or worse. So much I fear I will be dragged away that once, in a fit of terror, I begged my master if it were true. But Einar promised, upon his soul, Eirik Raude had seen none.

As the ship's builders set the mast secure and strung the rigging aloft, to the harbor we went, me, Inga, and Groa, with the tight-bound roll of cloth resting on our hips. There the strongest men set the sheet upon the yard and raised it up, "Pull! And pull!" blinding white in the noonday sun. It rippled until they rigged it sharp, then flooded full with the wind's breath. We watched the new ship bound from the harbor toward the fjord's mouth. In a moment it was out of sight. From where we stood we could see no farther than the hill where the homestead lay.

Now I stand before that very ship, with only the narrow plank to tie it still to shore, foreign though it is, as my mother always told me, though now she's gone, buried beneath a shallow mound of earth, with a stone upon her feet to hold her still, and I am alone, with before me only the great black water and what lies unseen beyond.

On such a trip my mother once sailed, though with even less hope than I, for it was then she was enslaved. So she'd told me many times at night, whispering, while the others about the slaves' hall slept, and she beside me in the straw, her warm, soft body pressing close to ease the cold, the painful tale of the place from which I'd come, a place I've never seen, a land whose air I will likely never breathe yet of which she told me ever and again, until my thoughts and my heart call that place home.

They came along the Irish shore with the dawn, stealthy and silent in the mist. Only the smell of smoke through the house's thatching warned of them, and then the sound of clanking metal as the raiders took the town, hut by hut, farm by farm. My mother told how my father hid her in the filth of a pit beside their byre, from which she watched him bravely fight against these enemies with only his sharpened ax and then, when they'd cut it quick, only with its broken stem. He was bold but could do nothing against their heavy Viking swords. They were so many, so large and cold and fierce, and he was alone.

When they split my father's skull, my mother said the Vikings laughed, spattering the grass with his honest blood, kicking his writhing body with their hard, thick boots. Her cries she could not quiet, and for this she blamed herself, for then they found her and wrenched her from the hole where she'd been safe. She showed with pride the scars from where she fought their rough hands as they dragged her through her own husband's blood, blood which stained her dress, a dress she kept even to her death, in which I saw her buried. From a molting satchel hidden in the corner of the servants' straw, I took the rag and dressed her in it myself, and my tears through my hands brought up my father's blood as if it ran anew.

That day the raiders bound my mother and all the others up in chains, but buried deep beneath her dress was her beloved's final gift. And so I came with her to slavery and to this land unborn.

They'd come then and taken us in a mist of silence, secret as death. But this day there is no need for stealth. This day we stand waiting to depart in a spray of these freemen's Viking songs.

Well, through the jostle, tone, and bustle, I look about for Inga, my one true friend, like a sister to me really, though somewhat older and of a different sort, all round and red, short and stout and quick to laughter, while I am mostly of a straight and somber sort, and sometimes, though I do not mean it wrongly, sour. Still, she is the dearest to me since a child, who has known my every secret and kept them ever still. Even now, though I am fully grown, I long to feel her somewhat safe beside me. Yet she is none about me now - only some way off - yes, there! - I see her - attending to our mistress, Grima's youngest children. Torunn - she's the girl, and the boy, Torgrim - both sweet enough, and most well used to Inga's constant heeding. Yet now they are off, and Inga running in a flail of skirt and pebbles flying, hailing them with exasperated shouts, "Yea, Torgrim, get back! Torunn, you stay here. Torgrim, come ye back here!"

I would go myself to find him, for I run so much faster than Inga can. Yet I am barely from our line when I hear behind me, "Katla, think you 'tis your concern? Stay back where you belong." Nay, I know 'tis Hallgerd. Hallgerd, who finds her chore most fit to tell us all our rightful cares, though she is but a bonded slave herself. "He is Inga's charge," she jeers, "and well she knows just what to do. She'll do without you even better, for you know our mistress wants you not too close about her kin."

It is true, my mistress does not like me. Perhaps 'tis on my mother's 'count, yet I do not ask and dare not wonder. Instead, I stay within our line, for now it is moving slowly closer toward the shore. First we cross the last of moss and grasses, then upon the gravel's clack, then to stand before the creaking board - nay, it does but sway! And the waves leap up, sudden ranging higher from the deep, menacing there before my bundled feet as I take my final step from this Iceland shore.

I am pressed ahead, first by Hallgerd, then by others. It is but quick across, then I stumble on the wide-berth knarr. Trembling still, I catch myself. Each body's weight tips the vessel ever deeper. The fjord's waters rise, hugging close the wooden boards as I try to sit where I am bidden, between the bundles, crates, the bags, and chests, upon the rough and rocking floor.

Barely have I settled on a place when, down the beach, I sense a stranger watching. I know at once he is no slave. His stance wears a self-conscious grace, though his cloak is cloth, not leather, his cap soft wool, not pounded bronze. His look is fair and lean - a freeman, though a poor one, if I am any judge. Yet at me, his mouth is set agape, on his lips an almost speaking, his fingers reach as if to catch my own. He sudden presses through the throng. I draw back sharply, calling quick for Inga. Almost he is at our ship, but she is nowhere by. Yet, when he hears my voice, he bows his head and murmurs, "I am sorry," turning, shrinking fast away.

Strange, for he turns again several times, even as he tends his burdens, loaded up with sheep and goats and other goods in a wind-washed chest. Twice he has to thwart his goats upon the rut, and nearly loses a lamb with no one else close watching. He turns and smiles softly as I try to hide my laugh. Then he is gone, lost among the crowd.

Now, at last, comes Inga, breathless, up the plank. Her skirt is soiled and she is bent, fretting over poor Torunn. "Katla, take this Torgrim from me!" she begs as Torunn retches over the side. "Nay," Inga coos, "Torunn, already? Even in this little waft of sea?"

Torgrim squirms within my grasp. "Katla, think you my father - will he send us off upon the deep alone?"

Einar still stands on the shore with the other chieftains, setting fires and sacrifices up to Odin and to Thor. "Nay," I hush him, "of course he'll not. He but prays to have us make the safest journey." I press Torgrim close against my bosom, patting gently across his narrow back. Yet, after not too long, he wriggles quick away.

Escaping fast, he tries to climb the railing. "Father!" he shouts, setting out to leap just as the sacrificial flames set up to roar.

"Stay back!" I grasp him, falling hard across a pile of boxes. But Torgrim's close to me now, clinging, pulling some, yet starting up to shout, "Father, do not leave me!"

"Nay." I stroke his sun-bright crown, enduring the soggy damp of his tears soaking through my wadmal dress, and the breeze as it shifts and cuts now harsh across the shallow rail.

Another heavy step sets the vessel jostling: Einar himself, his broad shadow blocking the sun until he sees us, comes, bends, and pats his child's brow. "There, Torgrim, be proud and bold as a proper Viking. Now Thor's eye will watch our ship with favor. Hush you, so, and clutch upon our Katla. There, I know you like her well."

To me, he cups my chin within his hand. Then, at last, he turns upon the risen deck, where his high-seat stands. The helmsman Audun waits, his hands clutched on the steering oar. Einar sets to wave and gives the master's call. Then the walking planks are swept swiftly up. With their sturdy oars, the rowing men push the ships from shore. The gravel scrapes. The water slogs. Stroke by stroke, the pyre's flames recede.

Slowly the shoreline empties of all who've come to wish our masters well. Around me, cries burst from freeborn women, mostly matrons pressing sodden rags against their softly shriveled jowls. Too, even whimpers slip out from the thralls. Yet my eyes are dry. I cannot cry for loss of what I leave or in terror of where I'll go. It is all the same to me, for I am slave to them in either. My life will be no different, only the dirt which will be my grave.

We push down the harbor, the ships cutting the fjord with lines of foam like a loom's taut webbing, the rowers' arms gleaming soon with sweat, slowly reddening in the sun. My mistress, Grima, standing lean and haughty on the deck, notices me at last and beckons to bring Torgrim. With a foul look on me, Grima takes him back and props him on her lap, proud beneath the shade of the risen deck where her husband conducts the progress of the ship. Then she sends me off. I must stand now, for there is no place left to sit. All the thralls huddle where they may, in empty spots along the ship's cramped sides, or by the mast and yard, lying long and low within the hull beside the thick-furled sail. They are like a hefty pair of spindles, one twined around with threads, waiting only for the first brisk gust and the master's call to be raised up high. Yet for now we must bide with them as well.

A brace of wind cuts across the hull. Just beyond a mounded isle, there, behold the open sea! Though it is still far, the other ships fall into line beside us, and all let Eirik Raude's knarr take the lead.

There he stands upon his high deck, gesturing, calling orders we cannot hear. Eirik's figure's grand and fierce, his head and beard afire. They say he was always much the same - boisterous, unruly, outlawed in his younger days, first from Norway for killing in a temper, and then again from Iceland for doing much the same, which sent him adventuring to this place, this "Greenland," to which we all now follow, blind but for his flaming lead.

I look behind as each ship falls in line. Yet, as I do, feeling some and musing, I am caught again by that same freeman's watching. The ship - I think 'tis of Hafgrim's house - and there he sits upon the oars. His shirt's pressed back around his waist as he strokes in rhythm with the call. His is a bare, fine shape, and his deep-blue eyes are locked with mine - ah, they spark a frightening fire! Hot, I turn away and try to hide my burning cheeks. But when I look again, Hafgrim's ship is pulled upon the waves, tangled somewhere among the others, like small whorls dropped to weave the sea.

Swift, we cross the fjord heading toward the open water. Soon the lift-and-falling makes me sudden ill. With each stretch we put between us and land, with each thrust of the men's great arms, my stomach quakes, jolting back while I am thrust forward. I put my hand upon my neck and lay my brow just upon the railing. The cool of the shield helps calm a bit, but, almost as the sickness fades, my mistress tumbles forward, thrusting Torgrim into my arms. Then we three together vomit into the waves.

I offer the child back as soon as she is recovered. Torgrim's weight is heavy, and my own arms, sudden weak. Yet the mistress simply stares at me with an edge of condemnation. I am a slave and so, I suppose, not allowed to sicken. Yet Inga comes to me. "Here, poor dear!" she says as she takes Torgrim to her arms, wiping off the spittle from his lips. "There, I'll have him, mistress. You should go and rest, if it should please you."

Then Inga eyes me, "Hush!" and bids me, "Come."

"If only I might sit," I beg, "lay my head across my knees, or simply rest my limbs upon the deck."

Inga takes my hand and, with Torgrim in her arm, guides me gently to a place beneath the bow she's guarded quietly for me.

"Here." She holds a well-soaked rag. I squeeze what I can and drink, then Inga presses the dampness to my brow, all the while blocking the mistress' view with her own son's drowsing body. "If Mistress Grima knew, she would lash us thrice apiece that we should take their precious water before we've even left the home fjord," Inga hisses in a whisper, but with her touch she helps me calm.

Beyond the harbor rocks, Einar calls to raise the mast and then the sail. With its steady pull, at last I grow used to the rolling waves. The open water takes us. Inga helps me stand to see beyond the deck. There - the ocean, thick and black as an endless slab of obsidian, but fluid, cresting white to the very seam of the sky. I squeeze her hand and meet her amber eyes perched above her freckled cheeks, but we hear again the mistress calling, "Inga!"

"Likely Torunn has to piss over the side." Inga rolls her eyes as she runs away to the mistress' shout. Yet I am almost well now, beginning to enjoy the waves. I thrust my face into the wind, so hard and fast my ears ache from it, but I do not care. I feel almost that I am flying.

Then a hand falls on my arm. I do not turn. I hear his voice. "So, is this lovely Freya standing here?"

I keep my eyes toward the sea. "You think it wise to match the goddess with a slave?"

With his thick, coarse hand, Einar's eldest son, Torvard, turns me roughly. "Katla, with name so hot, why are you so cold?"

He grips my chin with such a force I have to look at him: at his slack, grizzled cheeks and his weak, small mouth with its breath smelling thick and putrid. Torvard holds me, smiling. I am not sure what he wants, if he might bite my face or try to kiss me. He works his fleshy fingers harder and harder into my jaw.

"Torvard, come!" Einar shouts from the high-seat plank. "Leave the girl alone!"

My heart is pounding. Torvard glances toward his father, then groans and lets me go. But before he leaves, he raises up my amulet. "'Einar owns me,'" he reads the runes with a vicious lilt. Then he whispers, "Remember, one day it will be me."

My face throbs in all the places he's touched me. I bend to the rail, feeling the cord choking at my neck. Against the metal of the closest shield I press my cheeks. Still I know they watch me, these others, as they always do: the thralls in condemnation, the young freemen with their blood between their legs, and the freeborn women in jealous rage at Torvard's lust for me. Every farmer's daughter to the very highest rank seems to strive to steal his attentions away; while I would gladly give them, gladly be rid of Torvard, with his foul breath and his rime of sweat and his stench of urine and mead. But he is the master's son. For a freewoman with ambitions there could hardly be made a finer match. All the families know it. Yet what have they to fear from me? I am but a thrall, a reluctant toy for a man who is but a boy, filled with his new-grown strength and all too eager to shrug his father's binding fingers from his thickened neck.

He is but nineteen. He will not marry till he's twenty. In another year. How I wait for that day! Though I know well enough it will not save me. If Torvard willed, he could take me to his loins right here and now, and ever after, whether I wished to linger there or not. Only his father contends to protect me while he can, for my mother's sake; I know she begged it of him often. She knew, as Einar does too well, that Torvard is neither wise nor gentle nor loving, as he himself was to my mother.

With our lot it is all the worse to be pretty, and I am fair, fairer than I would choose. I am tall like my mother, and shapely, with her long copper hair that curls with the damp. Some have said I might rival even the fairest maids of the finest houses if it weren't that I'm a thrall. But I do not know, having never really seen myself save in the mistress' own silver bowl, which, when I rub it hard until it shines, still shows me but a strange, distorted vision.

Just once, when we were sent to the water to help clean some fresh-caught fish - it was a clear, calm day then, with the sunlight bounding off the fjord's water. The stench was up to my elbows and down about my knees, and globs of pink flesh stuck to my dress when Inga laughed and bid me follow her to wash in a shallow pool. There I bent and would have dropped my hands in fast if Inga had not caught my wrist and held me, saying, "Look. That's why the others stare so cruelly when Torvard comes."

And I saw, only for an instant before the wind stirred the image, a face like those I thought only goddesses wore. Inga touched my cheek, and I knew she wiped away a tear, but then I smelled the fishy stench, and both of us laughed, thinking how silly such passion could be roused for a stinking fish-girl.

But since that time, I have tried to see that vision again clearly and for longer than before. Some have called me vain, but it is not so much that as curiosity, especially as the time has passed and daily Torvard troubles me more and more, until it seems even his father, Einar himself, is hard-pressed to keep him back. Torvard listens with far less care than Einar is due, simply because he was fostered by Eirik Raude.

Now there is none to Torvard so great as that man. Since his return to his father's stead three years ago, there has been no peace. Constantly they are fighting over how a man should be: Einar is moderate and calm in all his dealings, while his son seems to mimic his foster-father's airs, being wild and bawdy and headstrong, affecting whims in manner and dress. If he could dye his blond hair red he would; but happily he cannot. He is no Eirik Raude. Eirik, despite his wild temper, has wisdom, too, and a sense of righteous justice. The crimes of Eirik's youth were made to protect what was his; Torvard's crimes, Einar fears, when they come, will be random and raging as the winds.

For that reason most, my mother tried to keep me safe, for it is not strange for a man to take a concubine. My mother was for Einar since the day he bought her at the Althing market; and well he treated her, as well as he might a slave; and even shed a tear when he learned last winter she was gone: dead with his child. Yet he knew she was never happy here. He'd always known, for my mother made no secret that she was not willingly a slave. Even in his arms, she said she never would allow him to forget she had once been free and always would be in her heart.

For her stubborn, still resolve, I think Einar most admired her. Often he told over the drinking horn the story of my birth, how proudly my mother dared defy him, giving me suck at her breast just at the moment he'd prepared to see me killed. If not for my mother's courage, I'd have lain exposed before the winds to fend until death took me to Thor's palace, Bilskirnir, where all thralls of the Norsemen go, or to the gentle arms of the White Christ, of whom secretly my mother whispered. But my mother would not have it so. I was her husband's child, the last she would ever have of him. She would not live to see me slain by the same cruel fate as he. This last she told me many times late at night, and then would kiss my forehead and say her Christian prayer, "Kyrie Eleison. Christe Eleison." By the Althing's law, once I was given suck Einar could not expose me. For that courage, he put me in her arms and said she could keep me. Mother always laughed in her telling then, saying that I howled out my lungs, which is why he named me Katla, for the mouth of the Norse's cold Hel.

Up till the day she died, he'd kept me safe and close, yet I can feel my mother's power waning. Her memory fades from Einar's thoughts like a shield that's begun to rust and crumble. Torvard's attempts since her death have grown bolder, while my master, consumed with plans for these new lands, pays less and less heed.

Now it seems only Inga stands by me. All the other thralls sit in wait and judge. I feel their eyes even now, as I sink down to the deck to rest my head against the planking of the bow. I gaze straight into their condemning looks. On this long trip, there will be no place to hide, so I will face them. We all do what we must. My mother did, and for me also. She gave her body so I might not give mine. For her I will protect what she has saved, even if it means they hate me and say I gad about as if a chieftain's daughter. How can they understand? They don't even remember from which land they came.

I am glad there are some new faces aboard: men mostly, broad-backed, with thick woolly beards and eyes as sharp as the sky, clear in their faces which are ruddy as if burned by the sun's distant fire. Some of their women already have cracked their chests' heavy locks to fetch a blanket or toy to keep a child from climbing the rail or up the mast. My master, Einar, is unused to such traveling companions, though in these past years he has traveled less about. Of late, he's been more farmer and husbandman of sheep than a Viking doing battle on foreign shores. Yet I've heard prideful talk at table of those days of raids and plunder and conquest and brave men now all gone to Valhalla. Often I would see my mother wince at his honor in such tales. Still, I know he does not fancy these softer days.

Nor does Torvard, who has yet to see such fight. Even now he anxiously flings his knife into the thick mast-pole. Forthwith, my master scolds him, "Beside this mast, only Odin's humor and Thor's strength will carry us again to land," and sharply withdraws the blade, angrily dulling it with his whetstone. Then he hands both back. "Here. Hone this, and keep your ire at bay."

I want to laugh, for Torvard is an angry fool, but, fearing he might see me, I bite my cheeks.

The ship bobs in the current as wind fills up the sail and sweeps us farther and farther from the home fjord. Audun, at the steering oar, charges the men still to work the oars to breach the rocks beneath the keel. Their stroking slaps barely sound in the heavy surf. Far in the distance, the land we leave is but a thinning line of gray.

There is one other on this ship, one I dare not cross or catch with an eye or even pass. From where I sit, she is far across the deck, but still I draw back in fear, and I see the others do so also. Even on this crowded boat we leave a wide circle of air around her, for it is said she knows the gods, that they twist her tongue and make her speak and whatever words she tells always come true. They call her Thorbjorg the Seeress, and say she comes alone, with no husband, no children, and none she leaves behind, with only her sheep and cattle and a handful of thralls and a chest full of gold got from the invisible ones she caters in their earthen mounds.

For some long while, she has lived upon a distant spit, far, but not yet far enough, from Einar's homestead. Well I've known but, grateful, never ventured, hearing oft of her evil eye, her evil hand, her evil foot. It is said that wherever she steps trips death, that her nights are filled with shrieking, that, where'er she goes, she mutters softly on the shadows' murk and sometimes spits and seethes upon her seeing.

'Twas one such sight, all weird about, on which she called a plague to sweep nearly all the farms at Arnarstapi. And the people there - those few who lived - in a rising rage burned Thorbjorg's household to the ground. It is said her 'stead was razed before, in Norway long ago, upon a famine's fate. Hard, she fled from there to Iceland - first to Herjolf Bardsson's farm, then, after this last plague's burning, to my master, Einar's place. Though my master never speaks such things; and sometimes Mistress Grima feeds her, sending provisions from our own short stocks. 'Twas ever other thralls who bore them, trudging up the fell-slopes and across the glacier's ashen fields, then returning, breathing hot with running terror, bearing back in shaking hands stinking, greenish ointments the seeress said would heal.

From the first, when it was rumored she would come aboard this ship, all the thralls in the house and in the fields clutched hard their amulets, put fresh herbs in their hair and pockets, spat in their shoes as they put them off for bed; but these things did not keep the woman from our deck. Our only comfort is that the others of her household do not sail with us. They are broken up among the other knarrs, for it was thought unwise to shelter all beneath one sail, dangerous all together on the same thin boards. Better to spread such dubious power about and lessen its potent' for harm. Yet now their mistress sits far at the rear, beside Audun, and I swear her lips are sparked with cants, and I see that her hands are moving - perhaps over a stick of secret runes.

At last, Einar calls the oars withdrawn. They set the sail at its tautest rig. The other ships pull close or pass us by, filling the sea as a sailing crowd. Great white billows puff up full and catch the wind. In the distance, I watch until the last of the land is gone, and only water, sky, and cloud and our ships fill my vision.

And then I breathe, not "I am leaving," but "I have gone."

Copyright © 2006 by Judith Lindbergh. |

|

|